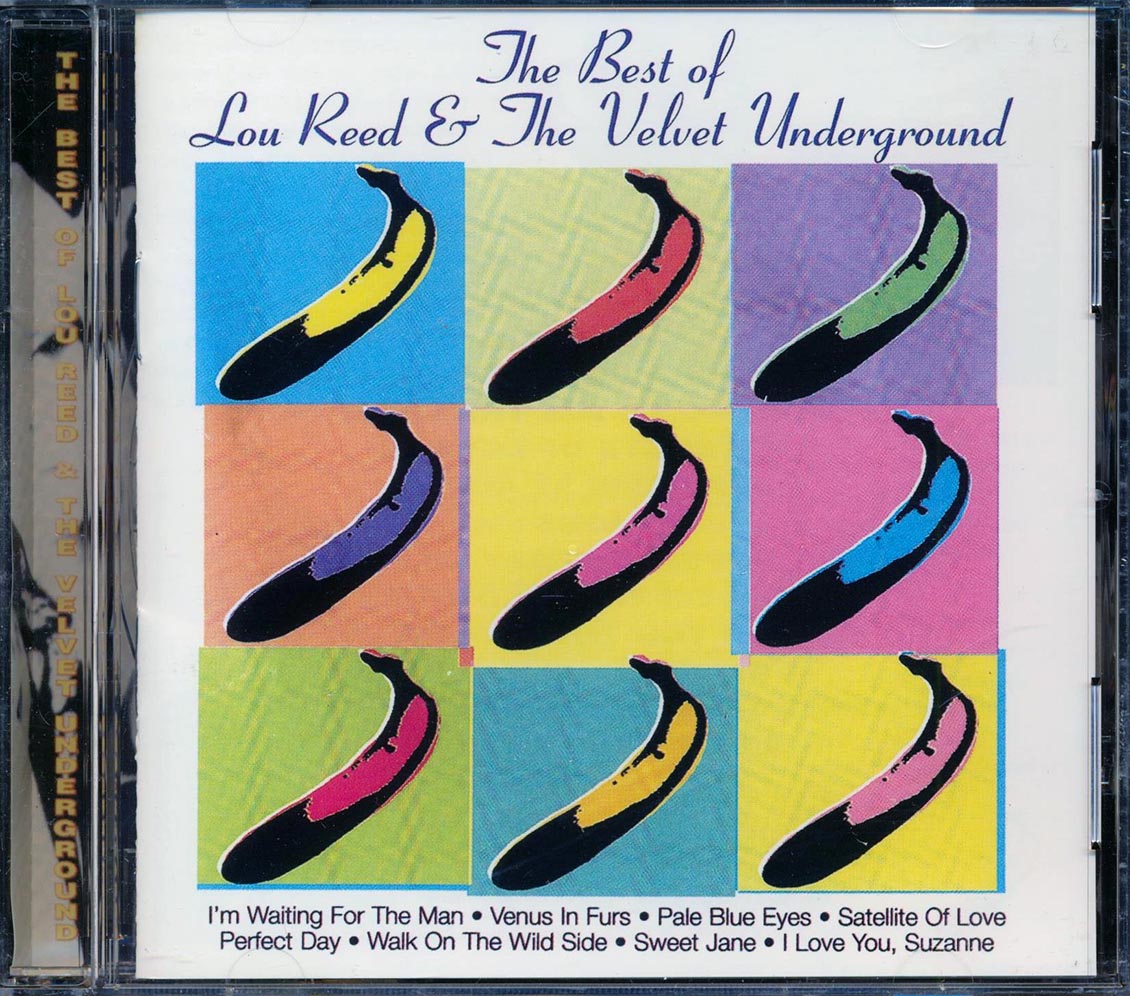

Reed points out how that was “in fact, more than I made with the Velvet Underground.” The famed DJ was out sick that night and Paul Sherman spun the disc, but the airplay netted Reed his first royalty check, for $2.70. Reed’s first record, “Leave her for me,” even got played on the Murray the K radio show. The snippet of the novelty song “The Ostrich” with Reed’s band The Primitives, and songs like it, are only an appetizer. Velvet Underground fans should be prepared before watching to delve deep into some of the early titles. A major high point of the documentary is hearing some of these early records. Educated on the melodies and chord structures of Tin Pan Alley composers, he started out as a low-rent house writer for the label, Pickwick Records. Reed was a rock and roller with a strong affinity for street corner doo wop groups like the Paragons and the Jesters. Reed didn’t like it, and would ultimately fire Andy, but it fitted the outfit for celebrity. Upon a suggestion by Warhol Factory superstar Paul Morrissey, Warhol added the hypnotic German actor and model Nico to the band’s mesmerizing sustains. It was, apparently, more effective for Reed than putting his hand through a glass door to get out of a gig he didn’t want to play on the St. Cale called the collaboration “dream music.” Modern Lovers founder Jonathan Richman says there were more noises coming from the stage than there were band members to account for. As evidenced in the drone of the viola of “Venus in Furs,” or the sustained chordal dissonance of “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” the harmonics create tones of their own. As opposed to the standard 440 pitch standard tuning, the 60-cycle hum, according to Cale, was “the drone of western civilization.” It affects the alpha rhythm of the brain frequency which then has a psychological effect on the listener. They found a home by tuning to the hum of the refrigerator at the Dream Syndicate space on 56 Ludlow Street. The most intriguing revelation of the documentary, musically, is hearing how the band settled in new places in sound. Warhol said that he liked the group because they sounded the way his movies looked. Warhol sponsored The Velvet Underground, putting lights behind them and producing their first album by merely coming up with the banana cover. We hear from Factory girl Amy Taubin that the Warhol clique only had time for women if they were beautiful, which is a disappointing, if not unexpected, revelation. Films like Bad and Trash put a gritty New York City edge to the campy cult classics of John Waters. Warhol’s film The Kiss extends time and expands inclusionary acceptance. This is partially because his films are obviously an inspiration to him personally. Haynes spends a lot of time on Andy Warhol. Yet, he still captures the period’s experimental tone. Haynes includes every scrap available, along with still photos and talking heads, to make the documentary chronological and straightforward. There is very little footage of the 1966 Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows, which is a shame because Warhol was noted for filming everything. The documentary uses split screens, like Andy Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls, but also clips of his other movies, including his Velvet Underground camera tests.

It earns its bona fides by including a smorgasbord of excerpts from experimental films. The Velvet Underground spends an hour in New York’s burgeoning and contradictory underground of the early 1960s. Velvet Underground drummer Maureen Tucker thought the “healthy-looking” Californians should “get real.” Named after Michael Leigh’s 1963 book about the sexual subculture, The Velvet Underground – Reed, Cale, Tucker, and Sterling Morrison – were as real as the city streets and as psychedelic as a Dream Syndicate. Because The Velvet Underground’s songs were about drugs and dregs, Zappa thought they were a group of heroin junkies looking for a banana to smoke. They even had a spat with their west coast counterparts, Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, who were also musically adventurous, and virulently anti-hippie. With The Velvet Underground, director Todd Haynes effectively evokes the Andy Warhol Factory’s experimental celluloid renderings, and captures both why Warhol was so taken by the band, and the reason the Velvet Underground were not made for factory settings.īoth Lou Reed and John Cage are renowned as antagonistic agitators, and the band had nothing but disdain for much of their contemporaries.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)